Types of cataracts

The three most common types of cataracts in adults are nuclear, cortical, and posterior subcapsular cataracts. Congenital cataracts are a major cause of leukocoria in infants and can lead to vision loss and amblyopia if left untreated.

Nuclear cataracts

Nuclear cataracts are the most common type. These usually manifest with blurred vision, myopic shift, and loss of blue/yellow color perception. They are most commonly associated with increased age, but smoking, gender, and diet may also influence their development.

Brunescent cataracts are very advanced nuclear cataracts that are opaque and brown. Their increased density makes phacoemulsification very difficult and increases risk of complications. Morgagnian cataracts are a special case of hypermature cataract (see page on cataract grading).

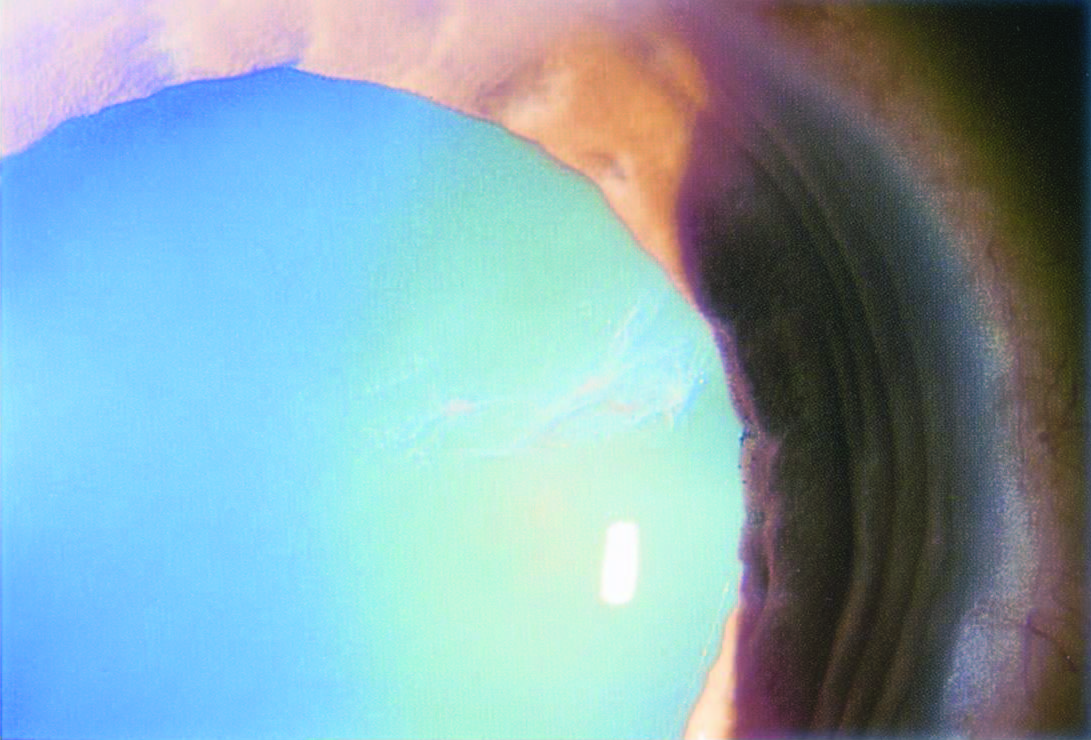

Cortical cataracts

Cortical cataracts are often wedge-shaped in appearance and located in the inferior or nasal aspect of the lens.

Symptoms include glare and diminished reading capacity. Risk factors include race (African Americans), diabetes, sunlight exposure, trauma, and smoking.

Posterior subcapsular cataracts

Posterior subcapsular cataracts occur just inside the outer lens capsule. These can be more rapidly symptomatic and may manifest with glare, diminished reading capacity and monocular diplopia. Younger patients are more likely to experience these cataracts than nuclear or cortical cataracts. Risk factors include glucocorticoid use, uveitis, retinitis pigmentosa, diabetes, radiation.

Congenital cataracts

These cataracts are opacifications that appear within the first year after birth. Causes may be either genetic, traumatic, or infectious.

- Any genetic mutations in crystalline structure can lead to cataracts.

- Other genetic conditions with increased risk of cataracts include familial congenital cataracts, galactosemia, Down syndrome, Pierre-Robin syndrome, Lowe syndrome, and Trisomy 13.

- Developmental insults that damage the nuclear or lenticular fibers can lead to total, polar (anterior and posterior), lamellar, zonular nuclear, or punctate cataracts depending on the region affected.

- Prenatal maternal infections such as rubella, rubeola, cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex (HSV), herpes zoster, influenza, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), syphilis, and toxoplasmosis can lead to congenital cataracts.

Numerous systemic diseases are associated with increased risk of cataract development, often with distinct patterns.

- Diabetes mellitus

Diabetic snowflake cataract - Diabetes is associated with increased oxidative stress.

- Glycation of ion pumps in diabetes also leads to increased osmotic stress and cataract formation.

- Myotonic dystrophy

- Almost all myotonic dystrophy patients have cataracts.

- Early cataracts are called “Christmas tree” cataracts because of the bright, branching appearance of fine dust-like deposits in the posterior lens.

- Deposits eventually cloud the entire lens and form mature cataracts that may be indistinguishable from other etiologies.

- Mytonic dystrophy can also be associated with “bulls-eye” macular depigmentation.

- Wilson’s disease

- An autosomal recessive disorder in which hepatic lysosomes are unable to store copper. Labs show low serum ceruloplasmin, low serum copper, high liver copper levels, and high urinary copper. The classic findings with Wilson’s disease are Kayser-Fleischer rings due to copper accumulation at the edge of the cornea.

- About 20% of patients with neurological signs of Wilson’s disease have “sunflower cataracts” comprised of a multicolor central opacity in the anterior capsule surrounded by radial opacities in the lens cortex.

Certain medications increase risk of cataract development. Prolonged use of prednisone (often for one year or more) may induce cataracts, particularly subcapsular cataracts, that require surgical removal. Miotics, chlorpromazine, allopurinol, chloroquine, and amiodarone can all also contribute to cataract formation.

More examples of cataracts associated with systemic conditions: